![]()

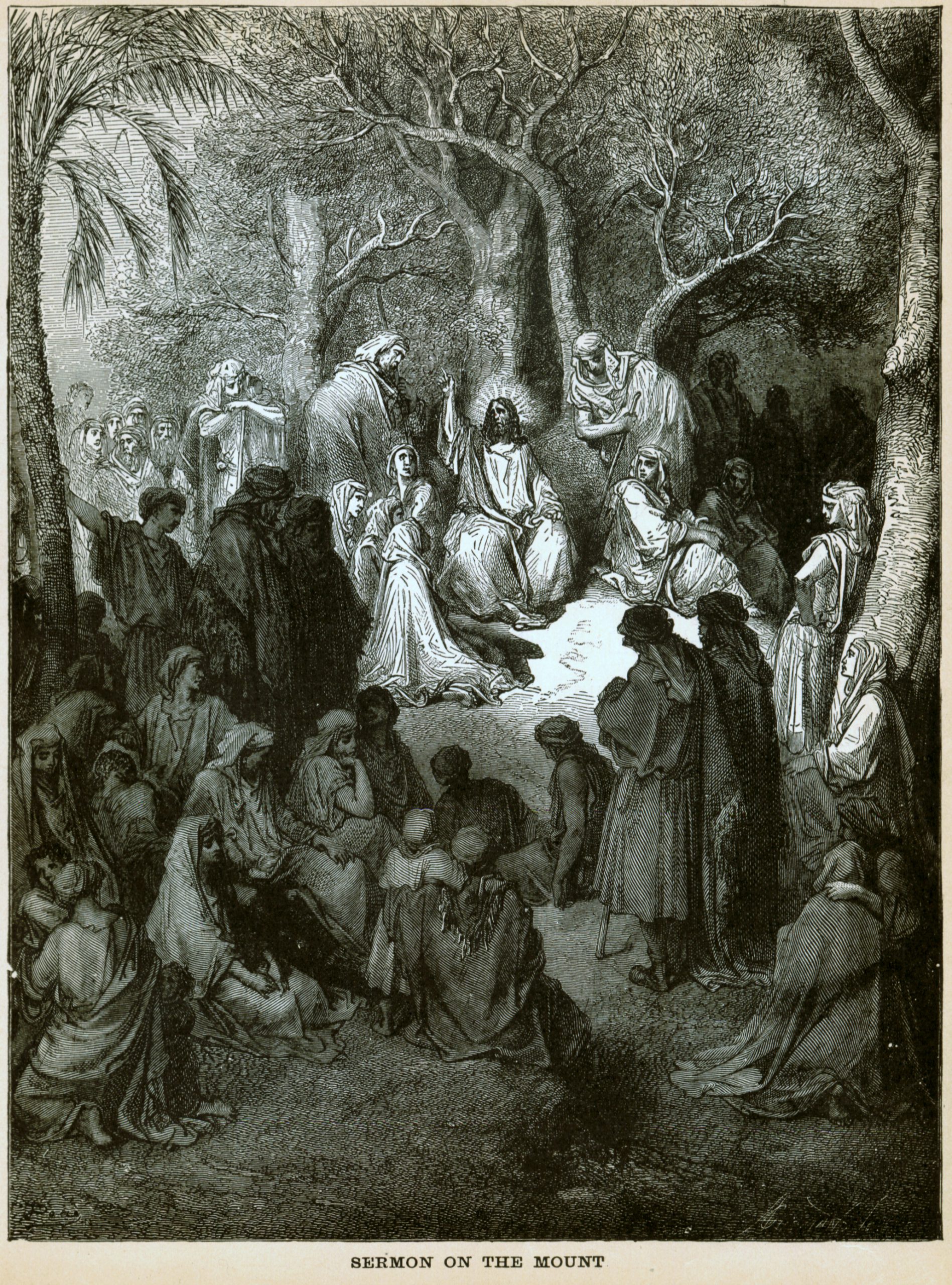

In our last edition, we discussed the Sermon on the Mount. There, Jesus explicitly taught faithful observance of the Torah or Law and emphasized its lasting status by referring to a rabbinic homily about the “jot” and “tittle.”

We will now deal broadly with the six contrasting statements Jesus made in the same Sermon. Each begins with, “It has been said . . .” and ends with, “but I say to you. . . .”

For example: “You have heard that it has been said, ‘An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth’; but I say to you that you resist not evil; but whoever shall smite you on your right cheek, turn to him the other also” (Mt. 5:38-39).

The plain meaning of a statement such as this implies that the first assertion is inferior, incorrect, less valid, perhaps even untrue. The second declaration is superior. Essentially, it means not A, but B is true, valid, and so on. Jesus seems to be replacing the biblical principle of justice, “an eye for an eye,” with “turn the other cheek.”

If that is the case, however, these statements would seem to contradict Jesus’ earlier claim, “Think not that I have come to destroy the Law or the prophets. I have not come to destroy, but to fulfill” (5:17). Is Jesus abolishing the Law of Moses and establishing new standards or not?

The format “not A, but B” does not necessarily mean that B replaces A, at least not in the Hebraic context. This may sound counterintuitive, but it is key to understanding the Sermon on the Mount.

There are numerous statements in the Scriptures and in rabbinic literature that use the “not A, but B” format. They start with an assertion that is contrary to known fact, unusual, perhaps even outlandish. This is the “not A” part. It is made intentionally to catch our attention by defying what we know to be true in order to make us aware of an even profounder significance expressed in the second half, the “but B” part.

This common Hebraic literary device is the equivalent of underlining to emphasize a particular point. As the rabbis explain, it means A is not the main or most important thing, but B is the deeper or primary message (Berachot 12b). The “not A” statement doesn’t invalidate an earlier principle or fact. Rather, it helps to expose weightier issues in multiple layers of the Scriptures.

We will see how this works in two examples: The first from a rabbinic homily; the second from the Bible itself.

Here is a quote from a well-known rabbinic comment on the Scripture verse Isaiah 54:13 (emphasis added): “‘And all your children [banayich in Hebrew] shall be taught of the Lord, and great shall be the peace of your children [again banayich].’ Do not read ‘your children’ [banayich], but ‘your builders’ [bonayich]” (Berachot 64a).

The rabbinic commentator makes a statement that contravenes known fact, saying, “Don’t read the biblical text as it actually is” (i.e. “not A”) and suggests an alternate, “Read instead” (i.e. “but B”). One’s attention has been piqued by the commentator daring to alter a word of Holy Writ from “children” to “builders.”

Consider, however, the following: This change is accomplished in the Hebrew by replacing just a single vowel. Since antiquity, the Hebrew Bible in scroll form has been written without vowels. The vowel sounds were transmitted for centuries by oral tradition and only later notated by the Masoretes. A slight change of a vowel, as in “banayich” to “bonayich,” results in a completely different word with a different meaning.

An informed Jewish listener knows the commentator did not actually intend to amend the Bible. He simply wanted to convey an added layer of meaning, namely, that those who occupy themselves with the study of God’s Word are the true, spiritual builders of the world and increase peace.

Even more revealing, God too uses the “not A, but B” format several times in the Bible.

Here, one example: “Thus said the LORD of hosts, the God of Israel: Add your burnt offerings to your sacrifices and eat the meat! For I did not speak with your forefathers, nor did I command them, on the day I took them out of the land of Egypt, concerning burnt offerings or sacrifices. Rather [or but], it was only this thing that I commanded them, saying: ‘Hear My voice, that I will be your God and you will be My people; and you will go on the entire way that I command you, so that it will be well for you” (Jer. 7:21-23).

Displeased with the continual sins of the people, God tells them they might as well eat all the offerings themselves, including those meant to be wholly burnt on the altar, as they are no longer acceptable to Him.

God then makes a startling statement. He says He did not command Israel about burnt offerings or other sacrifices when they left Egypt (v. 22; “not A”), but only told them to obey Him for their own good (v. 23; “but B”). Is the first part true? Surely not.

Remember that, in preparation for the exodus from Egypt, Israel was commanded regarding the Passover offering (Ex. 12:3-11, 21-27). At the giving of the Ten Commandments, God commanded Israel regarding an altar and offerings (20:21; some translations v. 24).

Also, on Mount Sinai for forty days and nights, Moses received commands to build an altar (27:1-8) and instructions about offerings for consecration, atonement and the daily offering (note especially 29:1-46; 30:10, 20, 28; 31:9; see also 40:29). It is obvious that God did, in fact, command Israel about offerings and sacrifices from the time they left Egypt.

Since God does not lie, what does it mean? As previously mentioned, “not A, but B” means the following: A is not the primary aspect, but B is the primary aspect. What sounds like a non-factual statement (“I did not command Israel regarding offerings”) is, in fact, simply a means of emphasizing the weightier matter, namely, that obeying God is primary.

So, though sacrifices are valid (they are, after all, God-ordained), one should not become routinely dependent upon them, lacking sincerity. Sacrifices are secondary inasmuch as they are part of the corrective process after sinning. In fact, obedience obviates the need for many sacrifices.

With a Hebraically attuned ear, we can now understand what Jesus meant in the Sermon on the Mount. He was not changing the Law’s guidelines for judges to act with judicial fairness. Rather, Jesus’ primary concern was man’s inclination to seek revenge.

In daily life, man’s nature is to exact measure for measure propelling him into an unending cycle of hatred or violence. Often, this leads to litigation before judges. But courts are, at best, a limited remedial measure to restore damaged property. They usually do not succeed in eliminating festering grudges between feuding parties. A meek spirit, concessions, even silence in the face of insult and offense will in many cases obviate the need to litigate and will lead to broader communal peace.

This understanding of the “not A, but B” format has ramifications beyond just the Sermon on the Mount. Consider another example: Paul, addressing Jews, says: “For he is not a Jew which is one outwardly; neither is that circumcision, which is outward in the flesh, but he is a Jew, which is one inwardly; and circumcision is that of the heart, in the spirit, and not in the letter; whose praise is not of men, but of God” (Rom. 2:28-29).

Taken out of its Jewish homiletical context, this text has become a classic proof text for replacement theologians (supersessionists) to substantiate their rejection of Israel and claim of substitution by the Church.

But Paul, who saw profit in circumcision (3:1-2), and who circumcised a disciple named Timothy (Acts 16:1-3), obviously did not reject his people nor the precept of the Law concerning circumcision of the flesh. Rid of replacement theology abuse, the text is simply stressing the primary aspect, which is to serve God with a circumcised heart, meaning with love and willing submission, a concept known since Moses’ days (Deut. 10:16; 30:6; Jer. 4:4).

Reading Hebraically (in a Jewish context) can help Christians to understand more correctly both the Tanach (the Old Testament) and the New Testament, including Paul’s epistles. Historical misconceptions about the Jewish people will be alleviated, ideas that all too often are transferred upon Israel today.

*a rabbinic homily